Historical Landmarks

The guitar, which became a six-string simple instrument around 1800, will experience a flourishing period due to the enthusiasm of the bourgeoisie for this intimate instrument with a soft and sometimes melancholy sound, honored in the romantic European salons, especially in Paris, London, and Vienna. The two most striking personalities of the first half of the century are Fernando Sor (1778-1839) and Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829), succeeded in the second half by Luigi Legnani, Napoleon Coste, and Joseph Kaspar Mertz. However, around 1880, the guitar will gradually be marginalized in the face of the increasingly dominant influence of the piano, as evidenced by the composition treatises of Rimsky Korsakov, Gevaert or Lavoix who consider it to be an accompanying instrument.

It is useful to briefly mention the main guitar methods of the 19th century authors as well as the instrument-making at the turn of the two centuries in order to better understand Pujol’s method later.

To meet the demand of many amateurs, several methods will emerge in the last century, including those of Dionisio Aguado, Ferdinando Carulli, Mateo Carcassi, Giuliani and Sor, the latter being the most comprehensive method of the 19th century. As for the organization of lessons, one can say that Carulli’s method is based on the same pattern (scale, arpeggios, chords, study) applied to all major and minor keys and some pieces at the end of the method. Aguado’s method contains preliminary note-reading exercises; many exercises ordered in paragraphs, short studies, numerous linked and ornamented exercises, and more significant pieces at the end of the work. Forming a coherent whole, this method has trained many guitarists and has been the subject of more recent reissues (revision by Sainz de la Maza, for example). Sor’s method, on the other hand, bases its statements on analysis (anatomy, physics). The text is dense and the sketches detailing the positions are numerous. It is, as he states, “a treatise of the reasoned principles on which the rules that must guide the operations are based”.

The sound aesthetic differs among them: Carulli, Aguado, and Giuliani recommend using nails to obtain a brilliant game and velocity adapted to a virtuoso repertoire. Sor, Carcassi or Messonnier advocate the use of the flesh of the fingers, more likely according to them, to express the musical meaning of their works. Tarrega will join over the years this idea of pure sound produced only by the flesh and after him, some of his disciples including Pujol.

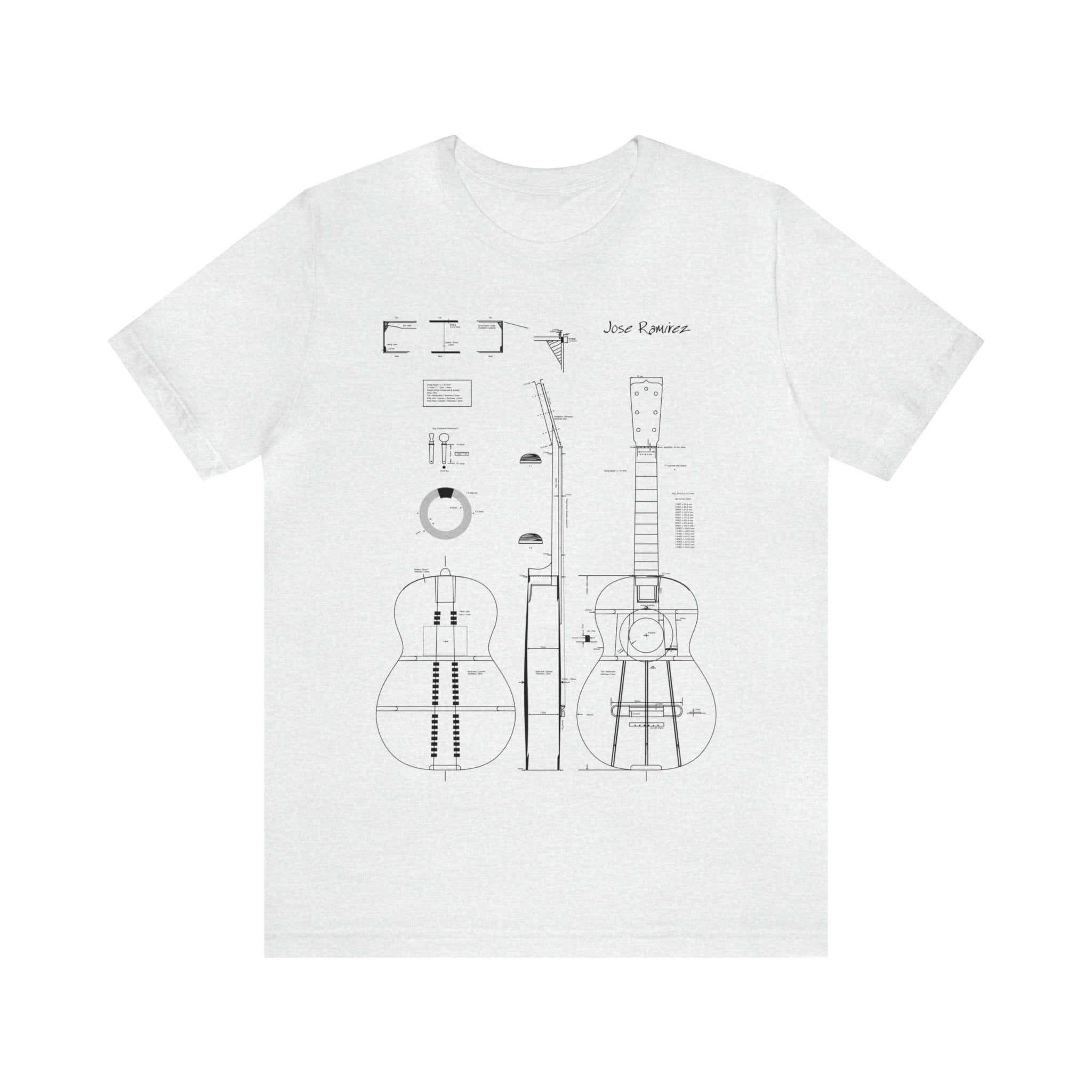

In Spain, research aimed at improving the power of the instrument will result, thanks to the luthier Antonio Torres (1817-1892), in the 20th century Torres guitar. Torres is responsible for the current dimensions of the guitar, but also and above all for its sound qualities: power, dynamics, and timbre. He reinforces the soundboard with small sticks arranged in a fan shape, adopts modern mechanics and works on the power of the projection of sound. Julian Arcas (1832-1882), a very important interpreter and composer of his time, will collaborate in its development. The imprint of these guitars can be found in all modern construction, both in Spain and elsewhere.

Francisco Tarrega (1852-1909)

was born into a modest family and was drawn to music at a young age due to his precocity and threatened vision. At the age of ten, after hearing the great virtuoso Arcas playing on a Torres guitar named “La Leona”, he decided on his vocation. In his youth, Tarrega lived a bohemian life, immersed in popular music. He earned a living by playing and freely improvising on the guitar and piano with popular songs and opera tunes. The Spanish musical scene in the 19th century was dominated by Italian opera, except for the zarzuela and patriotic songs that emerged during the Napoleonic invasion. By 1850, concert societies, chorales, chamber groups, and cafes-concerts (such as those where Albeniz, Casals, and Armengol would perform) developed and revitalized musical life. The creation of the Madrid Conservatory in 1830 provided a framework for musical nationalism to flourish. It was there that Tarrega, at the age of 22, acquired a solid musical education by studying piano and composition. His talent was recognized after a concert he gave for the Conservatory professors, who were curious to hear the guitar, which was then considered a street instrument with no place in official education.

Hardworking and recognized concert performer, he traveled very little and preferred to perform in the limited setting of private auditions. Guitar enthusiasts would gather at the time in unusual places, such as the famous “vaqueria” (cow barn) of Leon Farré in Barcelona where Tarrega, then Llobet, Pujol, Sainz de la Maza, and Segovia played surrounded by artists and intellectuals among whom were Granados, Vines, Vives, and Malats.

Tarrega composed exclusively for the guitar: preludes, studies, character pieces, and virtuosic pieces, written in a romantic language full of charm and poetry. He left many transcriptions that testify to his desire to act for the repertoire and prestige of the guitar.

In the beginning, he was inspired by the playing of Arcas, who himself was influenced by Aguado. From the age of 17, and throughout his life, he played on a Torres guitar from which he drew all possible effects. His research led him to question his entire technique and to abandon the use of nails in 1902 in favor of a sound produced solely with the pads of his fingers, the “better reflection of the soul.” He modified the position of his right hand so that each finger, which was quite stretched and perpendicular to the string plane, was at the same distance from the string plane, allowing the use of the ring finger on the same level as the other fingers, which was not customary at the time, and to obtain equal ease of attack. Tarrega favored the “butted attack” meaning, not diagonal but parallel to the soundboard, which gives the sound homogeneity and power. Here is what Pedrell wrote in 1915 about Tarrega: “He made one of the most expressive instruments in music out of an instrument whose resources seem so poor in appearance.” The technical renewal that Tarrega imposed was the result of his high musical standard and his desire to develop what in his eyes seemed to be a major asset of the instrument: its sound and expressive qualities.

In his book “Tarrega, Ensayo biografico”, Emilio Pujol sheds light on Tarrega’s mindset, reporting some of his reflections.

Here are a few:

“No work can offer the surprise of a procedure that has not been solved immediately to this technique”.

Pujol says: “The didactic spirit of the Tarrega school applies to solve in advance all the problems that may arise from the elements that contribute to the execution of a work: instrument; hands; mind (spirit).

“Demand perfection from the beginning, before having stored material in quantity” or “Play little and well at the beginning, then a lot and always as well”.

The attention paid to the quality of execution and attitude towards work can be observed. A significant place is given to precise analysis of difficulties:

“The difficulties are of two kinds: those that can be avoided, and those that must be overcome.”

“The guitar is a talisman that opens the most hermetic but sometimes also the most precious doors”.

The guitar offers a means of flourishing and achieving art. However, several paths are feasible; Pujol notes:

“A good school can make a good technician, but the artist will always be above any school or system”

Tarrega’s students took on the task of transmitting his knowledge: Domingo Prat in Buenos Aires; Josefina Robledo in Brazil; Daniel Fortea in Madrid; Pepita Roca in Valencia. Two of his disciples will influence the development of the instrument: Miguel Llobet (1878-1938) and Emilio Pujol (1896-1980)

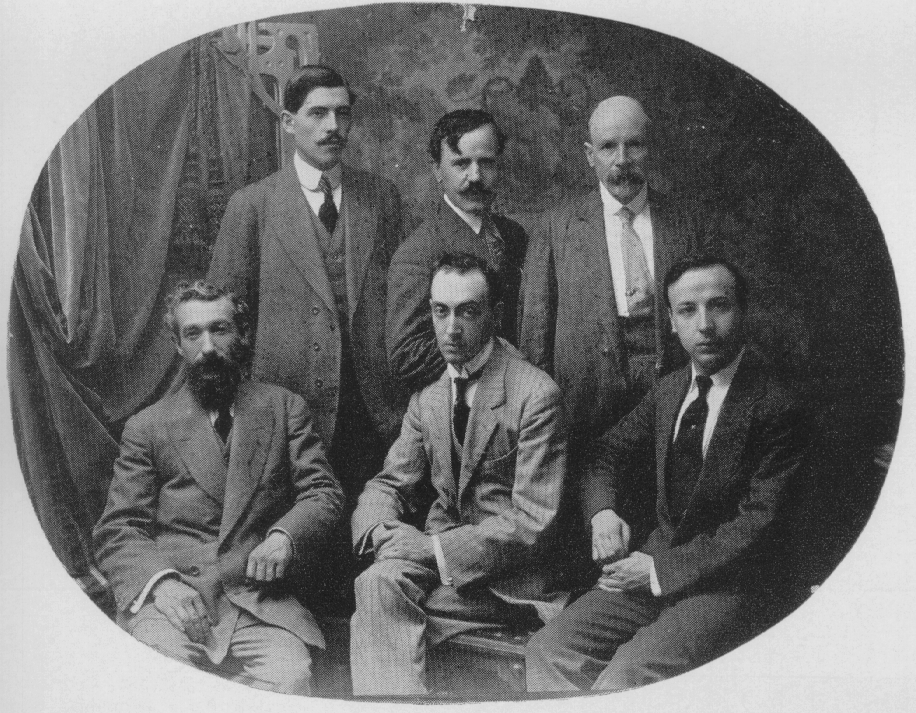

Enrique Garcia célèbre luthier, Miguel Llobet and Emilio Pujol.

Llobet had a brilliant international career. His compositions stand out from those of his contemporaries due to their sometimes daring harmony, influenced by the French musicians he frequented in Paris. In 1920, he created “Hommage to Debussy” by Manuel de Falla, of which he was the dedicatee and instigator. His most famous student is the Argentine guitarist Maria Luisa Anido. Pujol also had intense international activity, embracing several fields ranging from interpretation and composition to musicological research and pedagogy.

Classical Guitar